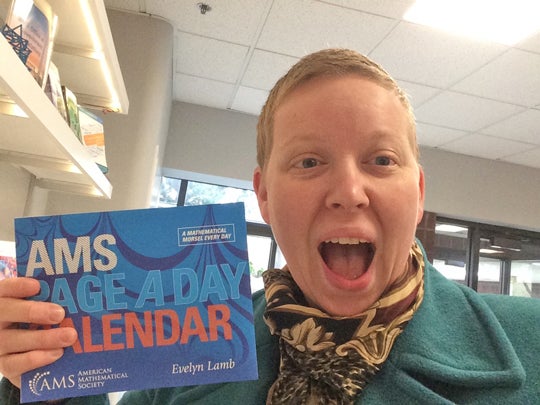

Freelance science writer Evelyn Lamb ’12 was headed for a career in academia until she spotted an email in late 2011 advertising a communications fellowship for graduate students in the sciences that the American Mathematical Society was co-sponsoring in Washington, D.C.

“It’s just something that had not occurred to me as a thing to do,” she recalled. But it was appealing. “Even though I had managed to finish a Ph.D. in math, doing that deep dive and concentrating on one thing was never my biggest strength.”

She’d always loved reading and writing. So she posted a last-minute application. Though she couldn’t have imagined it at the time, the decision proved life-changing. It landed her a three-month writing fellowship at Scientific American, one of the world’s premier science brands. Though she went on to an academic postdoc afterward, she kept writing and eventually realized her side gig had become her main focus.

“My research and teaching were getting in the way of what I wanted to do with writing. So I left my postdoc a semester early to see if I could do it full time. It was a little bit of a leap of faith.” And it’s paid off. Lamb’s stories have been published in Scientific American, Quanta, Nautilus, Science News, Slate and the Chicago Tribune among others.

Professionally, her Ph.D. training has proven crucial. “Even in the science-writing world, there are a lot of people who are intimidated by math. It’s just a place I’ve been able to find a niche.”

She’s found editors are eager to run stories about math.

“People like to read math stories,” Lamb said. “If the math stories don’t make them feel dumb. A lot of people have the mindset ‘Math isn’t for me. I’ll never be able to understand it,’ which means they’re really ready to stop reading a math article. The trick, in my job, is don’t give them a chance to say, ‘I don’t get it. I’m going to stop reading now.’”

There is no proven formula for that result, but she knows she’s succeeded when “someone who doesn’t think of themselves as a math person can say, ‘I understood the big picture of why mathematicians would be interested in this. I understood a side of math I didn’t see before.’”

Revealing the human nature of math is often key, Lamb said. “How can I get through to someone who has a mental barrier up about math? Where are the entry points? Where can I stick my foot in the door, crack it open a little and let people see that this is a part of humanity?”

She said numbers were initially abstract ideas that people invented to describe the world, and those abstractions took on a life of their own when people realized it was possible to reason and think about them independent of the things they originally described.

“Math is about the human relationship to these abstractions,” Lamb said.

And her writing aims to reveal the human agency and biases that are embodied in math, from AI sentencing algorithms to the structure of a musical composition.

“Part of what I want to do in my work is to show that the way we use math is decided by humans at every level,” she said.