Error and failure are part of life. Learning from them and learning not to let them stifle creativity are some of the most important lessons that structural biologist and pharmaceutical consultant John Spurlino ’88 gained at Rice.

“There is a lot of failure in drug discovery,” said Spurlino, who earned his doctorate in biochemistry from Rice and worked in the drug-design industry for more than 30 years.

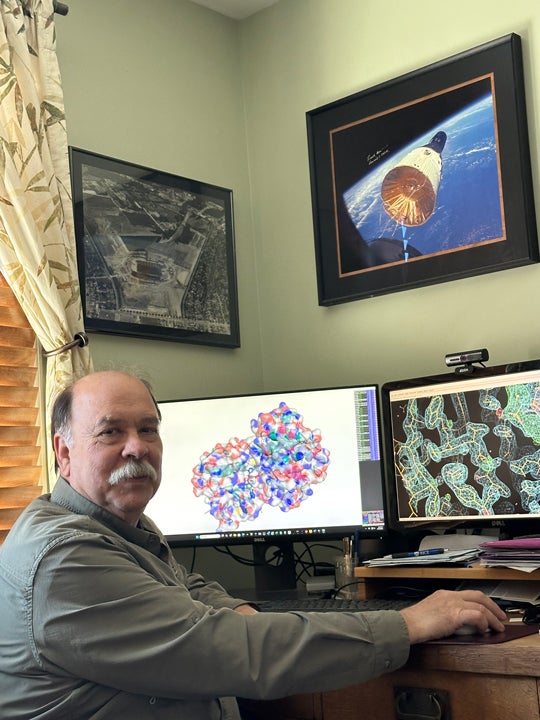

As chemical compounds that bind with proteins in our bodies, drugs are imbued with an inherent connection between their 3D form and function. Spurlino, a former research fellow for Johnson & Johnson and senior director at 3-Dimensional Pharmaceuticals, specializes in optimizing that form-function relationship via processes known as structure- and fragment-based drug discovery.

“As structural biologists, we know how things bind to the protein, and we can determine where to make changes to the chemical properties of a compound” to increase binding affinity, improve absorption, minimize side effects and more, he said.

He said he’s drawn to drug design, in part, because each compound is a puzzle that can only be solved with an intimate understanding of the complex interplay between biology, chemistry and physics.

Graduate school marked a return to campus for Spurlino, who first attended Rice as a 17-year-old freshman. Though he was intensely curious about mathematics and science, he had little interest in attending classes and left with poor grades after one year. Discipline followed. He put himself through night school at Wright State University in his native Ohio, earning dual degrees in computer science and chemistry. As a working professional and father, he took up martial arts, eventually earning a third-degree black belt.

Spurlino retired as the head of the structural biology division at Johnson & Johnson subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals in 2017, but still works as a consultant.

“I’m a one person company,” he said. “I just do consulting work. So I basically rely on my knowledge and experience.” Being a structural biologist helps, he said, because it allows him to forge connections between experts in other disciplines.

“There’s an interface between the chemists who make the compounds; the modelers, the computer-aided drug design people who model compounds; structural biology, where we actually see how things fit; and then biology, where you try to understand aspects of the chemistry that you want to change,” he said.

He said a measure of his industrial and entrepreneurial success stems from an important lesson he learned at Rice: Don’t be afraid to ask questions.

“True discoveries are made, many times, by being able to ask a question,” he said. “Sometimes, what you think is a stupid question, opens up doors of thought, opens you up to looking at things differently. And if you’re afraid to ask a question, then you can’t really expand on your knowledge.”

Spurlino said no single professor taught him that lesson.

“The biochemistry staff, when I was there, was just a phenomenal group of people,” he said. “They all had their own high points and their own skill sets. It was a combination, just being exposed to all of them.”

The caliber of Rice’s faculty is the reason Spurlino considers Rice “the best value in a school that there is,” and it’s a key driver in his decisions to support Rice’s endowment and to serve on the Wiess School of Natural Sciences’ External Advisory Board.

“I think Rice helped me a lot,” he said. “Even that one scandalous year as a freshman, I learned a lot there. As usual, many things that you learn, you learn because you’ve made some big mistakes. That’s the best teacher of all. I always told the kids, when I was teaching Taekwondo, ’If you don’t make any mistakes, you’re not trying hard enough.’”