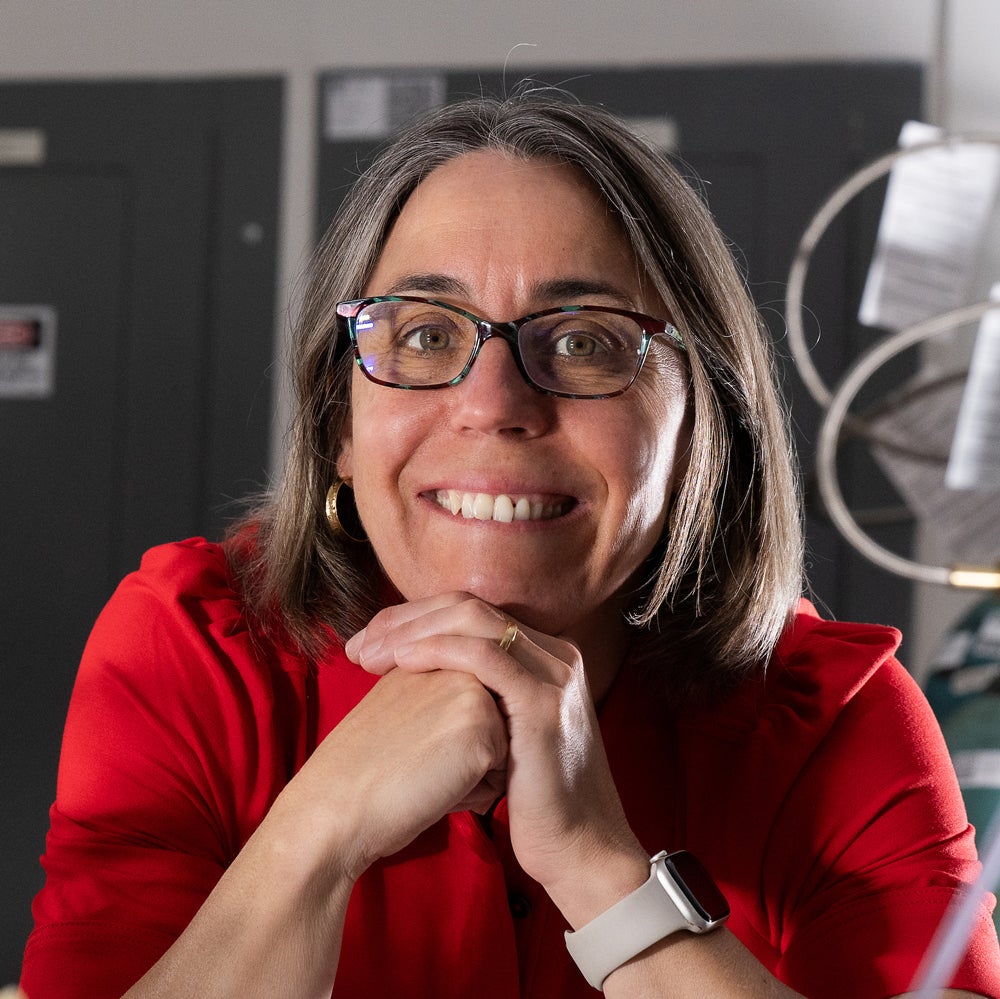

Caroline Ajo-Franklin didn’t always picture herself as a researcher. “As an undergrad, I remember thinking more of a career in teaching,” she said. “But I learned that I just loved being in the lab and the air of discovery.”

She was hooked by the thrill of asking questions that no one could yet answer. “I would rather wash dishes in a research lab than do any number of things. Even boring, dull work is just exciting in that atmosphere.”

Now the Ralph and Dorothy Looney Professor of Biosciences and founding director of the Rice Institute for Synthetic Biology, Ajo-Franklin leads a research group that has: engineered E. coli to act as living multiplexed sensors, discovered how some bacteria breathe by generating electricity and discovered ways to make customizable, living materials.

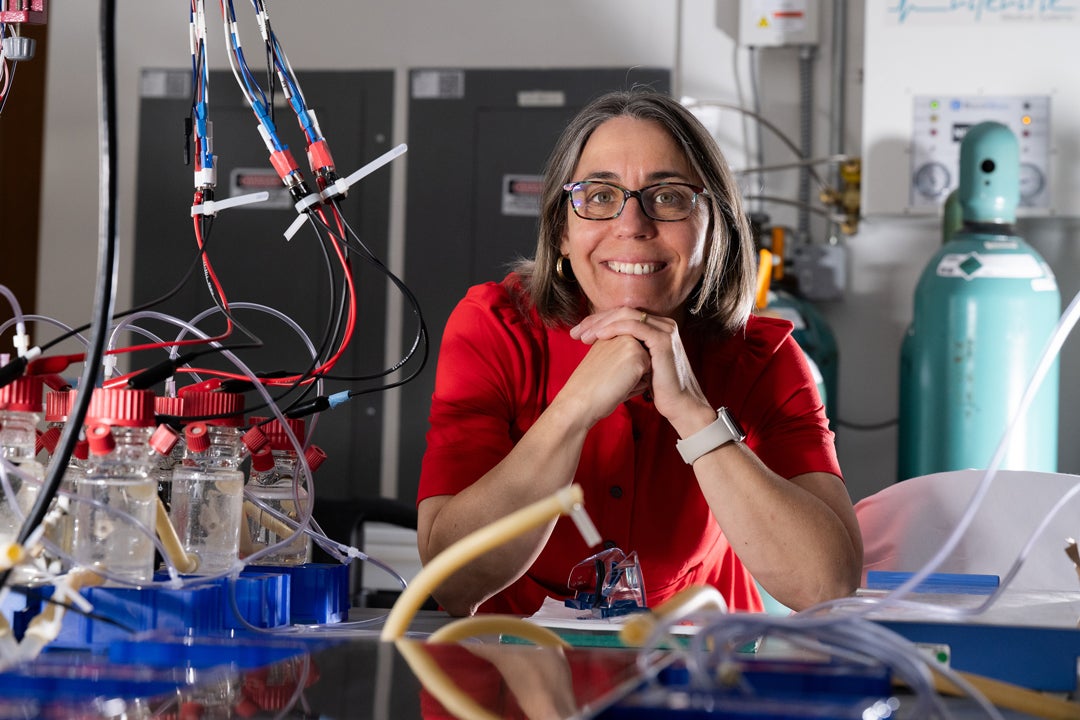

The lab’s central focus is exploring the interface between microbes and materials. “We want to understand and engineer that interface,” she said. “One of our main projects is on controlling electron flow between microbes and materials, because electrons are information in both electronics and within microorganisms.”

A second major focus is programming microbes to self-assemble into useful materials that have amazing properties. “We’re really dreaming of materials that grow themselves and change their properties based on, for example, sensing their environment.”

Imagine, for example, a porous membrane that seals itself when it detects a particular pollutant, cleaning water as it works. And when that membrane has finished its cleaning, imagine clipping off a small corner as a seed to grow a brand new membrane. “All the properties that you want are encoded,” she said. “That’s the dream.”

Her vision of synthetic biology blends curiosity and ambition with pragmatism and respect for nature.

“As humans, we are performing the largest uncontrolled experiment ever on our environment,” Ajo-Franklin said. “Biotechnology, I think, is going to be critical for continued human civilization. We’ve already seen how it improves human health. In the coming century, it’s going to be important for how we keep our planet healthy.”

But there are myriad questions about how that will happen, some of which cannot be answered in a laboratory.

“How do we deploy biotechnology solutions responsibly, in a way that really forwards our goal?” she said. “That requires international collaboration. It requires policymakers and scientists. And it really requires scientists to engage more thoroughly with the public than we typically have.”

Life, over 4 billion years, has “figured out all kinds of ways to solve problems,” Ajo-Franklin said. Discovering those solutions and finding ways to use them to address civilization-scale problems like climate change and biodiversity loss are just one part of the equation.

“There’s a real tension,” she said. “Biology offers solutions. But sometimes when humans have tried to implement biological solutions to technical problems, they’ve gone awry. We have to be humble and understand we are somewhat limited in our ability to predict outcomes.”

Her work with the Baker Institute reflects that balance. “If segments of the population do not feel a technology is safe, they will not use it,” she said, “and all that work was kind of pointless.”

For Ajo-Franklin, science is also inseparable from the people who practice it. Her lab is deliberately interdisciplinary, spanning engineering, microbiology, biochemistry and materials science. Just as important, it is deliberately kind. “It’s a bigger risk to be kind and to be sharing with your science,” she said. “We’re trying to promote that idea.”