From a young age, Andrea Isella was fascinated by stars. As an adult, his curiosity was drawn to what surrounds them: planets, and the swirling clouds of gas and dust that birth them.

His main research focus is planet formation, and more specifically the formation of planets that have suitable conditions for life.

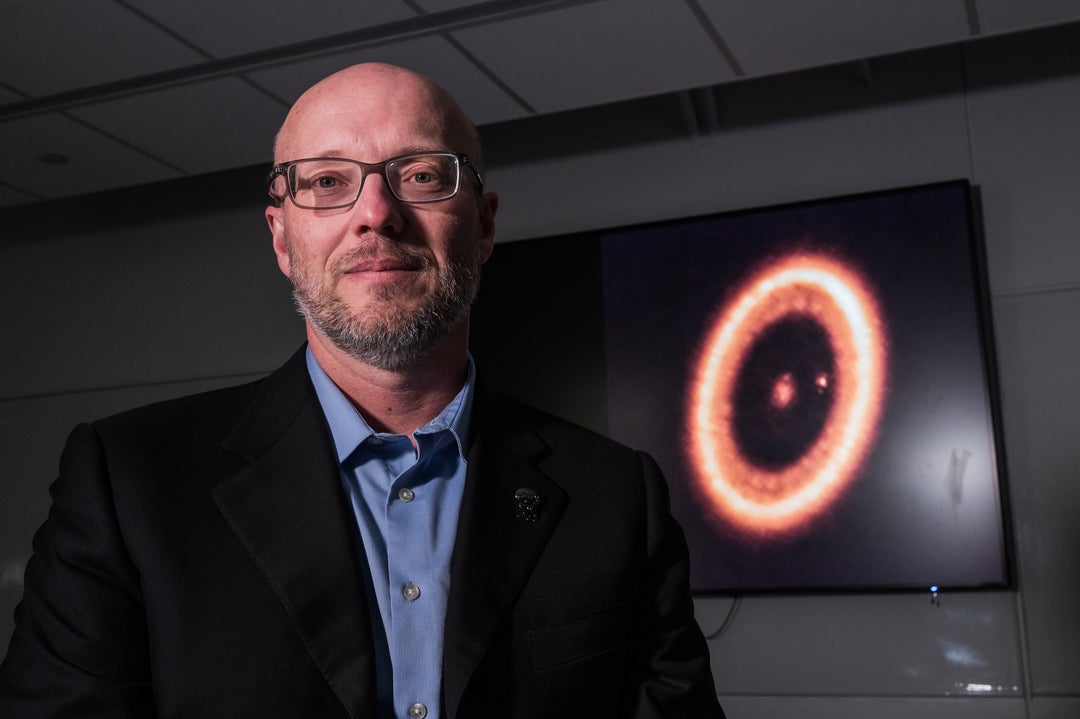

“As astronomers, our lab is the universe,” said Isella, the William V. Vietti Associate Professor in Space Physics and co-director of the Rice Space Institute. “We cannot touch it. We cannot change the parameters to see how the system responds.”

Until about 30 years ago, the only planetary system astronomers could study was our own. Since then, interferometry and other advances have allowed them to capture images of distant stars with sufficient resolution to discern planets, the size of their orbits and, in some cases, the types and proportions of elements in their atmospheres.

“We’ve figured out that, somehow, nature is capable of creating planetary systems that are very diverse, very different from our solar system,” Isella said. “That makes questions about how this diversity comes about even more pressing.”

The catalog of exoplanets has grown to more than 6,000, but astronomers are still searching for a distant planet that is truly Earth-like. That could be because planet-finding techniques have thus far been biased toward the discovery of much larger planets like Jupiter.

One part of Isella’s work focuses on observational studies of young stars that are similar to our sun. These provide examples of what our solar system might have looked like when Earth formed more than 4 billion years ago, which can help answer critical questions about how Earth formed and where its water came from.

“The chemical composition of planets depends on where they form,” Isella said. “If they form too close to the star, it burns too hot and all the water will boil off. If they are too far from the star, it’s too cold and water will be totally frozen.”

This gave rise to the idea that habitable planets exist in a narrow range of orbits known as a habitable zone. Isella said the concept is important but fails to account for conditions that undoubtedly played a role in the success of life on Earth.

For example, compared to today, the young sun would have been 20-30% cooler and emitted a more powerful stream of high-energy particles known as the solar wind. Earth’s magnetic field protects life on its surface from the high-energy radiation in solar wind, which can damage DNA and strip away a planet’s atmosphere.

The second part of Isellla’s research is a collaboration that aims to design and “build a telescope that can detect the magnetic fields of exoplanets and perhaps measure their strengths, which will tell us something more about habitability,” he said.

As the Rice Space Institute's director of research, Isella is working to promote more fundamental research at Rice related to planetary habitability and space exploration in general. For example, the institute recently awarded its first five graduate fellowships and its first postdoctoral fellowship for fundamental research, and Isella recently led a cross-disciplinary proposal for a NASA-funded astrobiology research center that would study the effect of a young, active sun on the evolution of prebiotic Earth’s atmosphere.

“We cannot see the young sun, but we can learn about it by studying stars like the sun that are much younger, and we can use this information to study how a young, active sun might have affected Earth’s atmosphere before life developed,” he said.